By Dan Schack

My original idea to publish a series of interviews through WGI on iconic controversial shows was spawned through one production alone. This production was one I was introduced to almost immediately into my own experience with the indoor activity. It seems as if watching it was a right of passage for the newcomer: a fundamental staple one had to experience to understand where exactly our small activity had come from, and perhaps, where it was going.

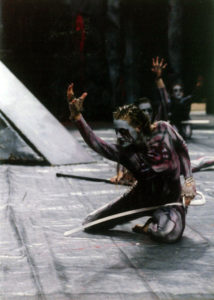

In 1997, Northmont High School, from Clayton, OH, tore the walls down with their fearsome production Dante’s Inferno. From the contorted humanoid forms, to the dismal and soulless set design, to the screeching and pulsating soundtrack, Dante’s Inferno is rid of reservation and apology. It succeeds wildly without overtly claiming itself as what it is or what it’s supposed to be. It is a world-made, engulfing the audience and the arena, welcoming them all into its demonic snow-globe.

I was incredibly lucky to catch up with designer Joe Sowders and director Tracy Wooton, who reflected back on a show that I am sure they have thought tremendously about in the 20 years since its final performance.

So I am writing to you from 2017, about a show that was performed in 1997. 20 years! My first question is, how do you think this show hails in comparison to what you see in the modern color guard activity. Does this stand the test of time? Is Dante’s Inferno still effective?

Joe: While I think it’s difficult to compare programs over decades, I do think Inferno has held up rather well over 20 years. I have always believed that for the viewer, the overall scope of the production sometimes overshadowed the individual skills that the performers displayed. The show had extensive equipment and movement vocabulary which was a large part of the overall effect. WGI crowds are smart. They know when something is just window dressing. Inferno would not have received the incredible reaction it did in Phoenix had the students not displayed World Class competence in everything that they were responsible for. So yes, I still think it’s effective today. It was designed to be a rollercoaster ride that would keep the audience on the edge of their seats. I think it accomplished that. And I think it would do the same today.

Tracy: It would absolutely stand up to today’s color guard. The show design and performance was way ahead of its time. The skill sets performed and the training was standard setting for the time. It is equivalent to today’s standards. We were designing in multiple dimensions. That does not even exist today. The visual weight of balancing the floor was a challenge of its own. In order to keep focus and draw the eye, special care had to be taken with performers 10 feet off the ground. Character, emotion, and the approach of the performer was developed correctly. It transpired to a genuine and believable performance, especially for those who saw it live.

For me, the first word that comes to mind when this show starts is theatricality. The overall commitment to every detail is evident here. Was your prop set up standard for those days? The costuming? The characterization?

Joe: I have a background in theatre and I always find myself leaning towards the dramatic when it comes to guard. Just as in theatrical productions, I believe the suspension of disbelief is a key element in guard productions as well. I don’t think of productions as a guard shows, I think of them as theatrical performances that utilize movement and equipment.

I was very happy with the costuming. We used greyish lycra full bodysuits that we took to a local artist who airbrushed the anatomical details. Each one was completely unique. I was also pleased with the makeup. The grey base was highlighted by the blood gel dripping down from the eyes (something I remembered from an old movie that I couldn’t resist). That combined with the hair gel wet look really gave the girls an air of intimidation that enhanced the characterization. I think we went through a 55-gallon drum of Dep Hair Gel that season! I remember the first time I had one of the girls come into rehearsal in full costume, makeup and in character. The reaction from the other girls was priceless. They couldn’t wait to do it as well.

The characterization was extremely important to the production. As a staff, we believed in setting the tone well before entering the floor. Once the girls were in costume and makeup; they were in character as well. From arriving at the arena, through warm up and on the ready line they were living it. We also had girls who interacted with the crowd during setup. I enjoyed watching the audience squirm in their seats a bit as the girls made eye contact with them.

The characterization was extremely important to the production. As a staff, we believed in setting the tone well before entering the floor. Once the girls were in costume and makeup; they were in character as well. From arriving at the arena, through warm up and on the ready line they were living it. We also had girls who interacted with the crowd during setup. I enjoyed watching the audience squirm in their seats a bit as the girls made eye contact with them.

Tracy: For the time, no one had more care to detail. The creation and production of the props took so many 3:00am nights with staff, artists and parents. The set up and tear down of props took orchestrating 70 people for show day and 30 people each rehearsal. Special effects such as the hanging took a special effects professional. Just getting all of that out to Phoenix from Ohio was a massive undertaking. The projects never ended but it was so worth it in the end.

The character of the performer was very complex. They would represent images of the concept as well as a real person in the setting. The role of the performer should never be clear cut. The best designs in any art form always allow personal interpretation from the audience.

The costuming really allows for you to explore both a literal character and utilize the body to create statuesque, distorted shapes. It is as if the body acts as part of the moving set design, each time they configure, the overall shape of the floor is reimagined. What was the intent behind the character of this show? Who do the performers represent? Is it even that clear cut?

Joe: I did want the girls to be able to meld in and out of the floor and set as needed. To be seen, and yet not seen. That’s why we had a base grey floor that we painted to be a cracked cliff. The textures and color of the props worked in the same fashion. The performers represented the tortured souls in Dante’s Hell. I envisioned the audience being Dante and Virgil as they take their trip though the underworld. In effect, the audience sees through Dante’s eyes.

Where did you derive inspiration for Dante’s Inferno? Why was this the year you produced this program? Had you had this idea for some time before designing it with this specific set of performers?

Tracy: When Joe and I started working together in 1995, there was a very specific plan. Dante’s Inferno was a natural progression of what we wanted to do in color guard. Specifically, “Make people forget they are in a gym.

With the 1995 Somewhere show, we took the performers off the floor and elevated them 8 feet off the ground. That was Northmont’s first standing ovation at WGI. In 1996 with the Vietnam show, we took a very theatrical approach. At this point, no one had really approached it this way. We still kept the performers elevated but in a different way. There was no drill, no real staging, the approach was more like theatre and we properly trained the performers theatrically.

So in keeping this approach in ’97 with Inferno, we knew we could actually create a mood. After the inspirational and tear jerking show from the year before, Joe decided we should shock, scare and maybe even make the audience uncomfortable. Brilliant!!!!

Joe: We were coming off the Vietnam show in 1996 which was a very successful season for Northmont. We felt we needed to take another step in our evolution. To try to push the boundaries in all areas. Many of those who went to war in Vietnam described it as a living Hell. I think that is what started me down the road to Dante’s Inferno. In March of 1996, a new interpretation of Dante’s Inferno was written by Robert Pinsky. There have been many interpretations of Inferno, but this one is a fantastic translation. It effectively communicates the journey with all of its gruesome details. Reading Pinsky’s Inferno basically sealed the deal for me. The incredible illustrations by Gustave Dore were also very inspirational.

Tell me about this soundtrack. It is extremely experimental: edging on some kind of progressive doom metal and spoken word. How did your soundtrack composition happen? Was this the effort of multiple people? What sonic elements did you utilize to create this heavily textured composition? What were the major places of inspiration?

Tell me about this soundtrack. It is extremely experimental: edging on some kind of progressive doom metal and spoken word. How did your soundtrack composition happen? Was this the effort of multiple people? What sonic elements did you utilize to create this heavily textured composition? What were the major places of inspiration?

Joe: One of the aspects I’ve enjoyed the most over the years is putting together soundtracks. But the soundtrack for the Inferno show was a serious undertaking for me. Besides depicting the show as a whole, I wanted to create a musical structure that the audience couldn’t predict. I didn’t want people to be able to get a feel for the pulse. To make that happen, I really had to create a completely new piece from a multitude of other compositions and vocal clips. If I had to narrow down the musical selections, I would say most of the material was from Elliot Goldenthal and James Horner. The vocal clips were from movies such as The Omen, Hellraiser and The Exorcist. I also used quite a few sound effects. Some of them were played backwards. The soundtrack was very challenging for the kids. The tempo (when there was one) was constantly changing with each musical selection, and it took much of the season for them to get a feel for it.

Aside from the bleak aesthetic provided by the material components of Dante’s Inferno, there are some disturbing, yet recognizable, elements and imagery throughout the show. Did you believe you were taking a risk putting these in at the time? Did you feel the show needed these elements to be fully realized?

Tracy: There were some very disturbing and recognizable elements of symbols and imagery throughout the show. That is up to the interpretation of people watching. Although we had a specific plan, I am sure that some of what was interpreted, was never intended. It was very important to the show. Many color guards produce effects, few actually establish mood and make the audience feel. During the hanging, there was a split second where when Jenny fell, I heard 10,000 people all breathe in. I think producing that is a lot harder than making people clap.

I am not a colorguard person so please excuse my lack of technical vocabulary! The overall choreographic style adds a certain texture to all of their movement that is angular, jagged, and frequently distorted from a neutral posture or even what one sees in a standard color guard show. Was this a technically proficient group? Was the training process for this specific show different than than your regular conditioning? Was movement most important for this show, or did you rely on equipment skills to get the desired effects of the program?

Tracy: The performers were trained using the Horton technique. Basically, Lester Horton viewed the human body as an instrument. Training the body to accept the skills. We trained the performers in both equipment and movement under the same philosophy. Both movement and equipment skills were equally important.

Did the performers at the time feel they were taking on a potentially controversial subject in their show? Did they embrace the design throughout the season? How did you convince them to buy in to something progressive or different like Dante’s Inferno?

Tracy: We really didn’t focus specifically on Dante’s Inferno with the performers. In order to teach character properly, the role had to be realistic and something the members could relate to. It couldn’t be legend or something intangible. We used a lot of examples of scenarios they could relate to, but none dealing with the book. These were all harmless and actually amusing. The kids had a lot of fun with it. The parents and members were completely committed to the show. The atmosphere in the gym was never dark. It was fun and everyone including parents and members were all onboard. All of us understood that we were putting on a theatrical performance, and there was never a time content or character was an issue in the program.

Towards the end of the show, you pull out all the stops with the performed hanging. At this same moment, (what sounds like) Rob Zombie drops, and the performers take on a very heavy metal style. Was this moment meant for irony? What was your intent behind invoking this contemporary and heavy music juxtaposed with this now iconic visual image of the body hanging?

Towards the end of the show, you pull out all the stops with the performed hanging. At this same moment, (what sounds like) Rob Zombie drops, and the performers take on a very heavy metal style. Was this moment meant for irony? What was your intent behind invoking this contemporary and heavy music juxtaposed with this now iconic visual image of the body hanging?

Joe: For me, the ending selection of Zombie by White Zombie was the payoff for the audience. After 4 minutes of disconcerting tumult, and the apex of the theatrics with the hanging, the only way to increase the intensification from that point was to move into a new musical genera. More of the same wouldn’t have worked. The selection was not only unpredictable, but it provided the perfect accompaniment to the shock of the hanging and the entrance of the hook weapons. Finally, the audience had something with a solid tempo that they could feel. The music gave the audience a mass signal that the show was designed to be over the top and it’s okay to go with it. Collectively, that was the point where the crowd stopped being observers and really became active participants.

To say this show has gained an iconic status is perhaps an understatement. I recall hearing about this show very shortly into my own career with pageantry, and it stuck with me even as a percussionist. Why do you believe this show has resonated so powerfully beyond its own time? Did you foresee this kind of reaction from the activity at large?

Joe: While the content has something to do with the reaction which has kept the show alive for 20 years, it was the approach to the content that I believe carries the most weight. We were determined to take everything to the most extreme level possible. If we were going to do this, we were going to do it all the way. A lot elements came together to produce something completely unique. If you remove any of the components, the show wouldn’t have been the same. But as anyone who actually saw the performance live can tell you, the girls really made the show what it is. They performed their hearts out in finals. From an emotional standpoint, they outperformed the window of what I believed to be possible for them at the time. Finals was the first time all year the show was elevated beyond the sum of its parts. Without the performers captivating the audience the way they did, we wouldn’t even be discussing this.

Tracy: I don’t think anyone could have imagined the long lasting notoriety of the show, although we did know every person in the arena would think we were completely crazy. I still can teach a brand new high school and when the students find out that I was the director, they get so excited and they weren’t even born yet. Every time this happens, I am still shocked. We were taking risks. We were not afraid to try something new. We were taking on a challenge of a multitude of props, a complex soundtrack, a complex show, a new way of teaching and we never let down.

What made this year special? Was this finals performance the culmination of many hands on deck?

Tracy: To produce a show like Dante’s Inferno, it goes beyond just having the idea. We needed support. We had a prop crew of 30 at every rehearsal. Our budget was small and the staff worked for basically nothing. The local hardware store donated most of the materials for the props. The high school shop teacher helped engineer, build and store them. We had the support of the athletic department and administration who allowed us gym space. The guard parents were fantastic! They held all the executive positions on the booster board and worked as the pit crew for marching band. They were responsible for raising the vast majority of the funds for the band program as a whole. They ran the concession stand at all stadium events and drove the semi-truck. We could not have produced anything without them.

What do you consider to make a show controversial? Do you believe this show is controversial? Does it even matter?

Joe: This is probably the most difficult question for me. When I think of the show today, I relate better to the word challenging. I believe this show challenged a lot of people. There’s no doubt it challenged us as a program. Both staff and members alike. It also was a challenge to the WGI community as to what guard can or should be. Everyone had opinions about Northmont that year and they spanned the gamut. I expected that. I wanted that. If you are producing art, and it’s not being talked about, you are doing something wrong. So in many ways, those that held the most negative and vocal views of the show were our biggest allies. The more people talked, the more people wanted to see us. The show was designed to be provocative and disturbing. That went hand in hand with the concept. But it was not designed to be offensive or insulting. Like waiting for a great rollercoaster ride, it made people anxious and nervous. Then during the ride, it scared and shocked. In the end, people cheered and yelled, “Let’s go again!”

I would like to thank Joe and Tracy for taking time to answer these questions!

About the Author: Dan Schack is an active designer and educator in pageantry arts. He is currently the Battery Co-Manager/Choreographer for Carolina Crown, the Artistic/Movement Designer for George Mason University, the Visual Coordinator/Choreographer for ConneXus Percussion, and a music and visual technician for Rhythm X and several scholastic percussion ensembles in the Dayton, Ohio area. Dan is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in English Literature and Women’s Studies at Wright State University, where he works as a Graduate Teaching Assistant. Dan has been a contributing freelance writer for Winter Guard International since 2012.