By Trudy Horsting:

Choosing the perfect show hair and makeup for a winter guard show is always an important decision. Still, it can be challenging to ensure that these choices are adequate for every member of the team and make every performer feel comfortable and confident on the floor.

In this piece, we sat down with two women of color with years of experience in the sport to understand their unique challenges and how we, as a community, can help mitigate them.

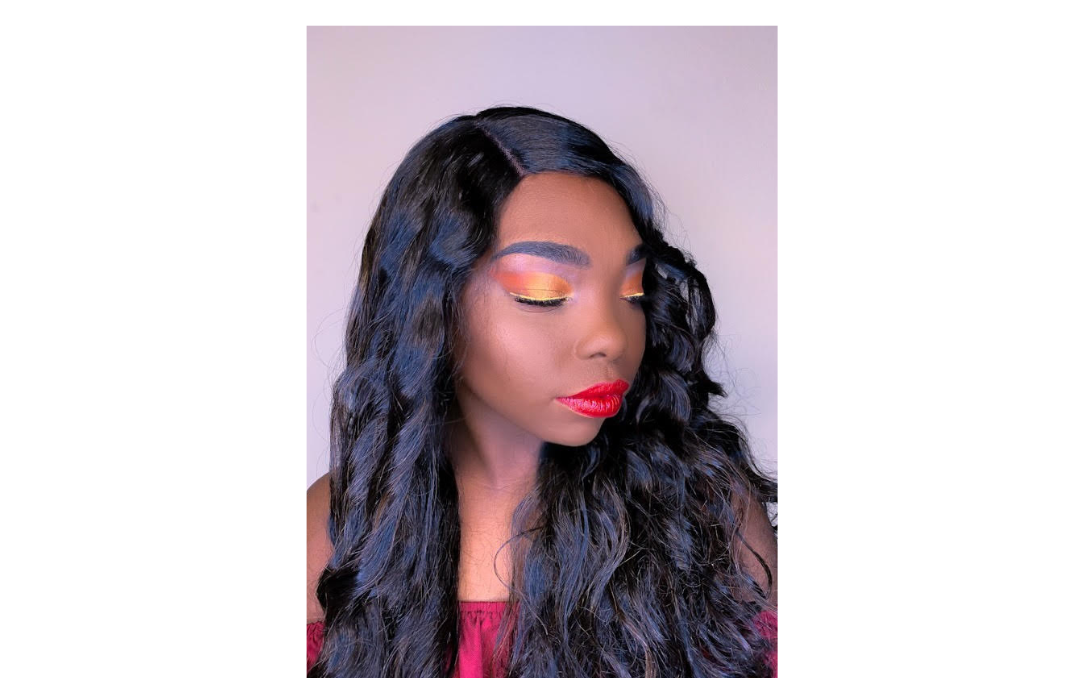

Aliyah Ingram has been involved in the color guard community since eighth grade and has marched at every level (A class, Open class, and World class). In college, she was a part of Eastern Independent, Carolina Gold, and then Legacy Independent, presented by Carolina Gold. Her career concluded after her final year at Etude. She has also taught and choreographed at a few programs around the Carolina region. She describes her experience as an educator as incredibly rewarding.

Sabine Francois’ marching career began in 2010, and she is still involved in the activity today. She started her career at Cyprus Creek HS and proceeded to march many great organizations over the next decade, including USF Winter guard (2013-2016), Phantom Regiment (2015), and the Cadets (2016). In 2013, Sabine began teaching at groups like Cyprus Creek HS, Freedom HS, UCF World, USF World, and University High School. Sabine speaks very highly of her experience in the sport of the arts; however, she nonetheless explains that there is always work to do as the activity evolves. She says, “I have had different directors and instructors that opened the doors early and provided diverse and inclusive environments so everyone could flourish.”

Through their experiences as performers and instructors of color, Aliyah and Sabine offer insight into what might have made their journeys through the sport just a bit easier.

Experiences with Makeup as a Performer of Color

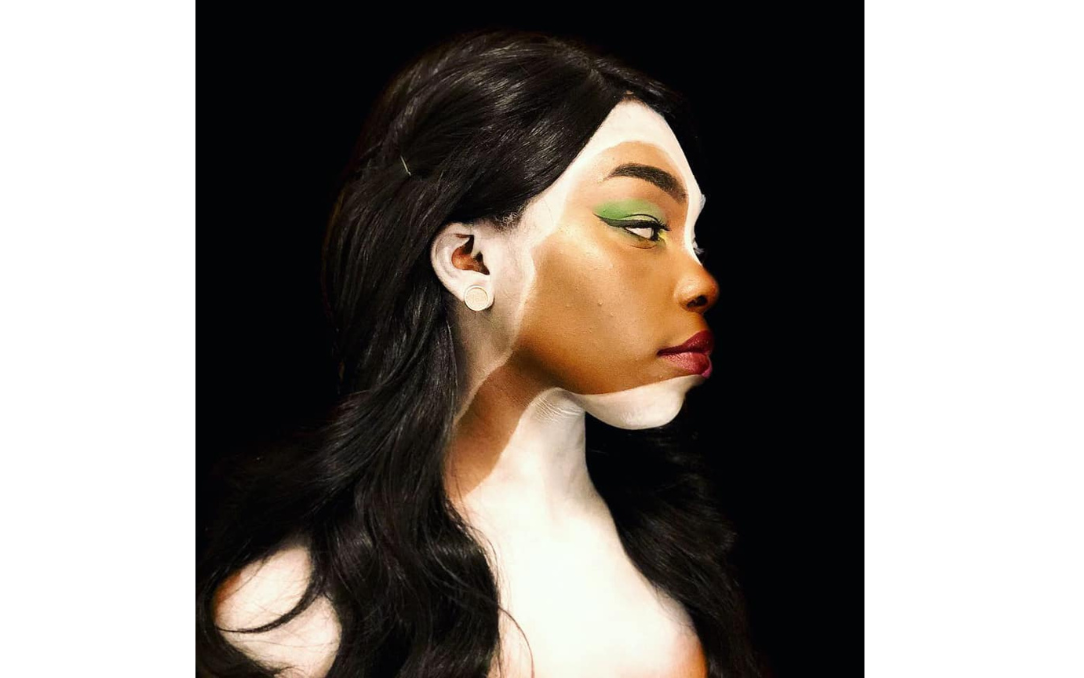

“Throughout most of my color guard career, the makeup I was assigned was not friendly to black skin tones,” Aliyah says. “I remember specifically in the eighth grade when we were asked to use a lavender eye shadow to match our lavender costumes. On me, lavender doesn’t look purple. It looks ashy.” Aliyah remembers looking completely different than the rest of the team. Unfortunately, her instructors never considered changing the makeup or helping her find a solution. She explains, “I played around with the coloring a lot and added a base color as a transition shade which made it look a little better, but it was a lot of trial and error to get to that point.”

Aliyah explains that color guard is the reason she became passionate about makeup. It started from a place of necessity. “If I didn’t want to look crazy on the floor, I had to take things into my own hands. No one told me how to do my makeup to match everyone else’s, so I had to learn independently. Now, it’s become second nature.” She explains, “Later on in my color guard career, if I was asked to do something, I knew exactly what I needed to adjust to make it work on me. Certain colors work on everyone without variation, like a dark smoky eye, but for the most part, I had to adjust the original show makeup for every production.”

Sabine’s experience is quite similar. She says, “Most of the time, the color pallets catered to the majority of the team. There were many pinks, purples, etc., but I never learned how to apply makeup properly to have those colors look the same on me.”

Aliyah explains that it was often a “fake it till you make it” scenario. “Eventually, faking it became second nature.” Aliyah reflects, “I haven’t thought about these things in a while but going back through those memories, I remember how I felt so alone in those moments. I felt isolated because I was the one who looked different, and that’s never a good feeling.”

Enough is going through a performer’s head on the floor that they shouldn’t have to worry about their makeup, hair, or costume looking different from everyone else. Further, feeling confident in those things can make a world of difference in their performance.

Experiences With Hair as a Performer of Color

Both women had similar experiences with their hair. They had to learn how to style their hair to match their teammates. Aliyah says, “Early in my color guard career, I had to manipulate my hair a lot. I’ve kept my hair natural since seventh grade, so, during my time in color guard, I’ve had to learn how to style my natural hair to achieve the desired look. Additionally, sometimes I had braids or would put in an extension and needed to figure out how to manipulate my hair when I had different styles.”

Aliyah reflects on how uncomfortable she was with many hairstyles, saying, “I remember worrying that my track was showing on the floor or that my lace was lifting. I would zoom in on every action shot to ensure nothing was wrong with my hair.”

She continues, “It was a lot of trial and error at the beginning to make sure my hair matched everyone else’s, and it never really did.” For instance, when wearing a bun, her bun would always be smaller than others on the team because she didn’t have the volume to fit her hair around a donut. Aliyah says, “My instructors were helpful, and they would hear me out on certain styles that I explained wouldn’t work for me. We would work together to find an alternative.” She explains, however, that the process wasn’t always easy.

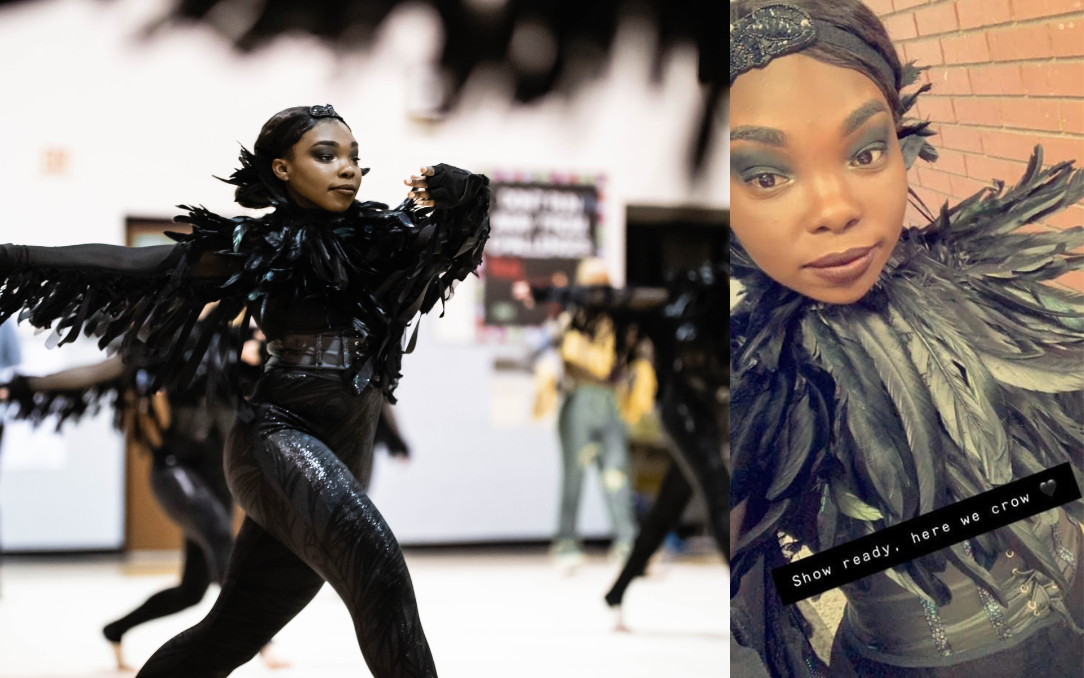

Sabine faced similar challenges with her hair. She says, “Show hair and makeup has been challenging for me. I’ve had natural 4C hair my entire life, and while it can be very versatile, it was never easy to recreate ‘European hairstyles.’ For example, if the team were doing a half up/half down hairstyle, I would have to press my hair every show, which was unhealthy. Due to this style alone, I experienced significant hair breakage, and it took years for my hair to recover.”

Sabine had many concerns surrounding the health of her hair throughout her color guard career. She says, “I take pride in my hair and how it grows. After the season where I had to press my hair, I promised myself that I would always try to find other alternatives.” She made an effort to show her instructors a variety of style options which might match the hair of the other performers but wouldn’t hurt her hair. She says, “I made sure to provide different options, like braids, twists, and natural twist-outs that would still provide a similar look to the rest of the team but would minimize the damage to my natural hair.”

In Sabine’s experience, “When it came to choosing hair, most directors would provide images of what they wanted to see. We would have a trial period to come in with show hair.” She says, “During that time, I would provide two styles that I knew I could have during the season, a natural hairstyle look, and one in a protective hairstyle, like braids or a crochet.”

Noticing and Becoming the Difference

Aliyah noticed a difference later on in her career regarding the inclusivity of styles. “Across the sport, people have been thinking more about inclusion. For instance, I had a great experience at Legacy because I marched there for so long. I had a great relationship with the instructors; they would brainstorm hairstyles and come to me to see if it would work. It was the first time I felt truly seen and considered, not as an afterthought. Comparing my eighth-grade season to my first season at Legacy is mind-boggling. At Legacy, I felt beautiful. It was the first time I had the feeling that my other teammates always got to have.”

She continues, “I never felt disobedient by speaking out, and they took the time to consult with me to see if their ideas would work. That’s probably when I felt the most confident in my hair and makeup because I was a part of the selection process and knew the choices would work for my skin tone and hair texture. It was helpful to be there at the drawing board.”

Advice for Performers

Although Sabine and Aliyah often stayed quiet early in their careers, they encourage current performers to speak up if they’re uncomfortable. Sabine says, “I would advise that performers speak up and mention the importance of having a style that will make you feel your best when performing. Educate everyone around you on the importance of representation and the value it carries.”

Aliyah feels the same. She says, “I wish I had the confidence and voice I developed later on at the beginning of my career. Over time I learned how to speak up if something wasn’t going to work for me and I was going to look crazy on the floor.” But Aliyah admits how easy it was to feel like a burden. “The instructors make the show, and I’m just performing it. And when I’m one of sixteen on the team, I didn’t want to be the one expressing that the makeup or hair wasn’t working for me.”

She continues, “As a black woman in color guard, we’re already a minority. I don’t want to speak for anyone else, but I always tried not to add any more attention to myself when marching. However, I feel like if I had the confidence to speak up sooner in my career, my earlier experiences would have been night and day.”

“If you feel uncomfortable or out of place, there’s nothing wrong with voicing your concerns,” Aliyah reassures. “Whatever information you share, ensure you present it with love and positivity, but never stay silent. It is emotionally taxing to stay silent and uncomfortable, and it’s amazing how much more enjoyable a season can be if you are comfortable. You deserve to be comfortable on the floor.”

Sabine shares the same sentiment, wishing she had been more vocal earlier. “If I could go back in time, in moments that I felt uncomfortable, I would pull the director aside and have a genuine conversation with them.” She explains, “I would present my concerns and provide other options, and I would try to educate the staff on the importance of hair health and different style options for performers of color. I’m a very solution-driven person, and I think it’s important to share options that I would feel more comfortable with and see if both parties can come to a place of understanding. These conversations need to be more common.”

Aliyah reiterates the importance of providing options that you know can work. “Know your hair type and what you can and cannot do. Learning what works for you will come through trial and error, but it will make your journey through this sport much easier.”

Aliyah similarly encourages performers of color to get familiar with what colors look good on their skin. “If you are ever in a situation where they require a makeup look that won’t work for you, you should be able to present similar options to your staff that works with your skin tone. It’s helpful to bring information to the table to help solve the problem, but the first step is speaking up.”

Advice for Instructors

People of color shouldn’t be an afterthought for the hair and makeup process or something that you try to “make work” after making decisions. Instead, deciding on hair and makeup should include a discussion of how these stylistic choices will fit all team members.

As an instructor herself, Aliyah says, “When you’ve been on the other side of things as a performer, and then you become an instructor and are making the decisions for a group, you don’t want anyone ever to feel the way you felt.”

Choosing Hair and Makeup

Sabine and Aliyah emphasize that performers of color must be part of the conversation from the beginning. Instructors should talk to their performers of color about what they need in addition to researching hair and makeup options. It’s also important to ask if your performers are comfortable. Most of the time, they won’t bring it up themselves.

Concerning makeup, Aliyah says, “From the start, you need to consider the look you are thinking about from two points of view. If you can make it work on a dark canvas, it will work on a lighter canvas, so I recommend considering the darker canvas first.” She explains, “It’s kind of like coloring. You don’t have to do extra work to get bright colors on white paper, but you have to put a base down on darker tones to get the true color you’re looking for. It’s important to think about this from the beginning.”

Aliyah also says, “Things are getting really inventive in the color guard world regarding hair. If you don’t know options that would work for your black performers, I would encourage you to reach out to any colleagues or associates of color to see what might work for them. Additionally, Google is a great resource to explore hair and makeup options for black performers.”

She also explains, “It’s important to remember that, even if a certain hairstyle works on a performer of color, it may look different than it does on individuals with other hair textures. For instance, if you want a slicked-back bun, it’s important to remember that performers of color will likely still have ripples and waves in their hair. If that’s not what you’re picturing for your program, you might want to go back to the drawing board and find something that will meet in the middle for everyone.”

Aliyah explains how helpful it is for the performers of color to be considered. Early in her career, she was never asked her opinion on makeup and was simply told to make it work. Sometimes, unfortunately, it just doesn’t work.

Sabine agrees. She says, “if instructors allowed us to have input on the styling of our hair, I think that would have helped tremendously.” You’re not expected to be an expert on hair or makeup, particularly for all races and ethnicities. What is important is that you are cognizant of the different needs of the various members of your group and work with them.

Additional Expenses

In addition to planning early and listening to your team, it’s crucial to let your performers know what will be asked of them as soon as possible. “Color guard is expensive, and so is hair and makeup, particularly for performers of color,” Aliyah states. “Additionally, many hairstyles take much longer for black performers, so the sooner we know what to plan for, the better. This way, we can get our hair styled to last the entire season without needing to be retouched or reinstalled.”

“Buying hair can be $200-$600, and many styles are another $100 just for the installation. This cost puts performers of color another $700 out of pocket, in addition to what they’re spending to march,” Aliyah says. Many instructors don’t think about this side of things.

Another thing that instructors may not consider regarding performers of color is that their hair needs to work outside of color guard. Many performers are in professional jobs that require a particular hairstyle. For instance, Aliyah is a medical assistant and isn’t allowed to have specific hair colors. Her hair has to be able to transition from the weekends to the work week. While some performers can wash out their hair after every performance, many black performers’ hair is more permanent during the indoor season.

Aliyah says, “When I marched with Etude, they did a fantastic job of letting me know what the show hair was going to be ahead of time. I would tell them what texture I was thinking about doing and ask if that would fit their vision. They would either say yes, or no, but if they said no, they would provide an option that would work. They had everything planned out ahead of time, so I was able to get my hair done the week before premier, and it was able to last the entire season.”

Sabine also talks about the importance of having options. She says, “I think it would have elevated my experience as a performer if, at the beginning of the season, instructors provided options for all hair texture types and tutorials on how to achieve the look. The best advice I can give instructors is to give options to their performers. As a performer of color, I have had to change my hair three to four times during a season.” Sabine recommends that staff discuss the look they envision for their team and develop three to four pre-approved style options that performers can switch between throughout the season.

We’ve Come Far, But We’re Not There Yet

It’s easy for performers to feel like a burden when a hair or makeup style isn’t working for them. Choosing hair or makeup that only works for some isn’t intentional, but by making better choices from the start, we can help all performers feel comfortable on the floor. Taking time to think about how to make the show costume, show hair, and show makeup, work for all skin tones and hair types can take a massive weight off the shoulder of the performers.

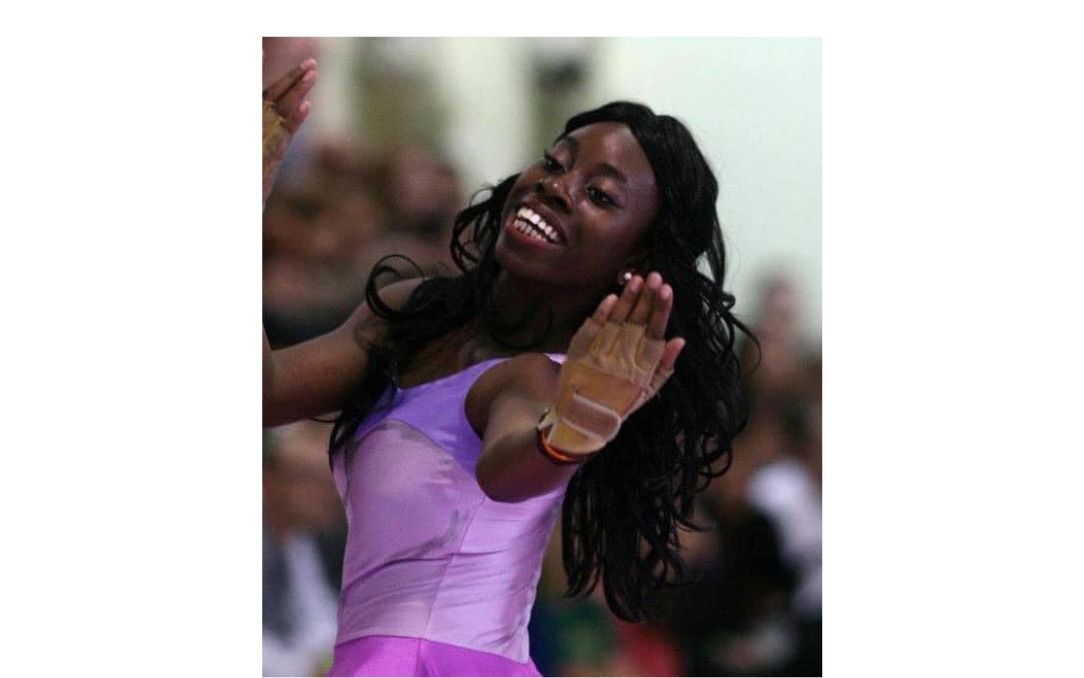

“There were times when I put on a smile to perform, but I felt like I looked crazy,” Aliyah says. “In my first three years of color guard, I had no idea there were different color body tights. I looked ridiculous because my legs were a light tan, and my dark feet were in contrast right below. I also didn’t know there were gloves for different skin tones.”

She remembers feeling so much better in hair, makeup, and costumes that suited her. “It felt so good to be in a body tight that matched my skin tone. I didn’t feel out of place on the floor and finally felt like a part of the team.” She continues, “In color guard, it’s all about being a part of the collective. If you look different, you don’t feel like you’re a part of that collective, and it’s a feeling that I wouldn’t wish for anyone. But, unfortunately, many performers of color will encounter that feeling at least once in their career.”

However, Aliyah is optimistic about the future. She says, “I’m hoping that with the rate of progress we have, that feeling is something that performers won’t encounter in the future. You have to be aware, and you have to be open to change and hearing the different perspectives of your team.”

It’s essential to educate yourself as an instructor regarding what building a diverse and inclusive culture is regarding hair. Sabine says, “If you’re uncomfortable, contact other instructors/directors who have had these conversations, and they can direct you toward resources and help you provide the best for your group.”

“Also remember that feedback is not criticism,” Aliyah emphasizes. Take all feedback with an open mind and an open heart. Remember that the goal is to make everyone on your team comfortable and, at the end of the day, if everyone is comfortable on the floor, it will make a world of difference for your show.”

The Future is Bright

Aliya reflects, “I remember the first time I witnessed a black girl being showcased in a show, and I’ll never forget it. It was USF Winter guard’s 2015 program “Swarm.” It was only my 2nd year attending World Championships. I was captivated to see someone who looked like me being featured.”

Additionally, the makeup design was stunning across every performer, and the costume suited every member. The confidence, joy, and comfort radiated from the soloist throughout the entire performance. I longed to experience that feeling of familiarity and trust. It impacted me profoundly and motivated me to speak up and advocate for myself and the other members of color to have the same experience as our teammates. I became the voice I wished so long for.”

“There’s still so much to grow, develop, and flesh out, but we’re heading in the right direction,” Aliyah says. In particular, Aliyah speaks about how many world programs have cracked the code regarding inclusive show designs. Contrarily, a lot more work needs to be done across younger groups. It all begins to change when we open up a conversation. Sabine says, “I have seen so much growth in the marching arts community over the years, and it all starts with conversations like these.”

Aliyah’s own experience through the sport is a testament to its evolution. She emphasizes, “I wouldn’t trade any part of my career at all. I’m grateful for all of my instructors, no matter how big or small the programs were. We all have to start somewhere, and while there were tribulations we had to work out along the way, each experience helped me develop into the performer and person I am today.”

Just a few small acts could have made a significant difference in those early days. “I truly feel as though something as simple as having someone to advocate for black performers would have gone a long way, allowing us to sit at the table from the start of the process.” From the makeup design to body tights/undergarments, down to the roles given in the show, it is a rarity that performers of color are included in the forefront of these design conversations. Aliyah encourages everyone to remember that they’re not a burden. She says, “Your voice and your comfort are just as important as any other member of that team.”

With a bit more forethought, planning, and open discussion, we can and will ensure that everyone is comfortable on the floor. Not only does this make a difference in the confidence our performers can exude during performances, but it makes a difference in the lives of the performers we care for.

About the Author:

Trudy Horsting is a graduate student at Arizona State University pursuing her Ph.D. in Political Science. She holds a MA in Political Science from ASU as well as a BA in Political Science and a BA in Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication from James Madison University. While at JMU, she was a four year member and two year captain of the Marching Royal Dukes Color guard and JMU Nuance Winter guard. She was a member of First Flight World Winter guard in 2019 and FeniX Independent World Winter guard in 2020.